Ikki Tsukuda, head of the Issa-an school, at a tea ceremony in the tearoom of the Suntory Museum of Art, surrounded by works by Aoki Mokubei (1767–1833), a late Edo-period potter, painter, and literary figure.

For the average Japanese, the word ocha (tea) doesn’t always call to mind the green powdered tea called matcha that is often associated with Japan. On the other hand, the phrase “I am learning tea” may conjure up images of the country’s traditional art of tea ceremony—specifically wabi-cha, a style that emphasizes simplicity and strict etiquette. The matcha used in this ceremony is blended with hot water in a tea bowl using an aptly named chasen (tea whisk). But when Japanese people say, “Let’s go have tea,” it’s often a suggestion to go to a café for a beverage, and that beverage may not even be tea—it could be coffee or juice.

Tea is commonly found on dinner tables around Japan and is often brewed from tea leaves in a cherished household teapot, although there has been a shift in recent years to using teabags or drinking bottled tea. In most cases, sencha (infused tea that is clear yellow to green in color) or hojicha (roasted tea that is brown in color) is served as families bond over their daily evening meal.

It appears that Japanese tea is also gaining in popularity abroad.

Japan’s food, health, and wellness culture attracted plenty of new fans during the COVID lockdowns, and if you fast-forward to 2023, you will find that matcha is now as popular as sushi in the US and throughout Europe. It is no wonder that more and more international tourists want to taste authentic matcha and experience the rich, almost mystical culture of tea in Japan.

If you trace the history of Japan’s tea culture back far enough, however, you will find that the tea plant and tea-brewing methods originated not in Japan, but in China. So, what exactly makes the Japanese tea ceremony so unique and special that it is now a major tourist attraction?

“Matcha is a ‘hospitality’ tea used in tea ceremony culture. The most refined way to enjoy this tea is in a wabi-cha ceremony. Wabi-cha became a common practice for the common people in the mid-Edo period (1603–1867), leading to the spread of a distinctive style of etiquette and social interaction guided by hospitality” (Ikki Tsukuda, Tea and the Japanese).

The book Tea and the Japanese discusses Japanese culture and the Japanese people in the context of two styles of tea culture: wabi-cha (traditional tea ceremony) and bunjin-cha, which is relatively unknown outside of Japan. We interviewed the book’s author, Ikki Tsukuda, who is the head of the Issa-an school, which has been instrumental in reviving the art of bunjin-cha.

—The art of tea ceremony is attracting attention worldwide as an integral part of Japan’s culture of hospitality.

Tsukuda:

The wabi-cha style of hospitality follows a pattern, with a cohesive driving force that draws participants inward to contemplate the essential nature of being human. Wabi itself can be described as an aesthetic, which wabi-cha followers fully embrace. Their commitment to perfectionism and conformity is widely believed to be a common characteristic of the Japanese people, but in reality, that is not true for all Japanese. There is also a distinct culture of breaking with form, allowing people able to express differing views and to frankly share their honest opinions, as opposed to putting etiquette first.

This is clearly visible in what is called bunjin-cha.

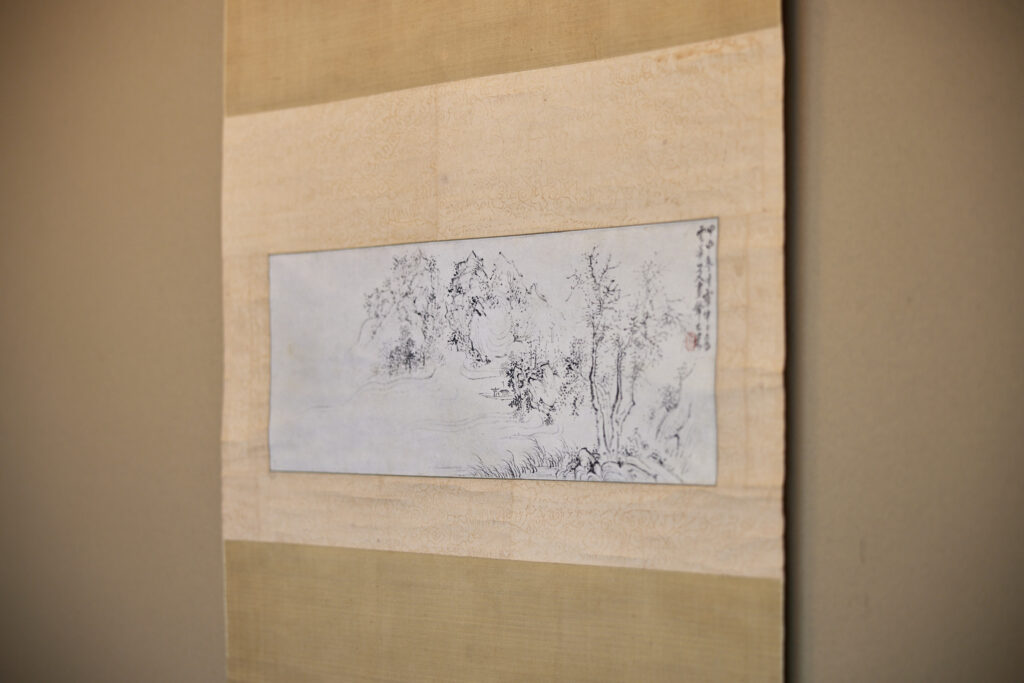

Mokubei’s Fishing in Autumn, which had been on display at the Mokubei Exhibition: 190 Years After His Death held at the Suntory Museum of Art, is being shown here during the tea ceremony.

In this style of tea ceremony the tea is made using tea leaves, which require a longer time to brew than the tea powder used in wabi-cha. In bunjin-cha, the time spent on otemae (preparing and presenting the tea) and performing the kata (ritual forms of movement) is very short. Instead, while the tea is brewing, an intellectual discussion begins, in which everyone is encouraged to expand their imagination by contemplating works of art, such as a hanging scroll with an intricate design. This is one of the quintessentially Japanese cultural aspects of bunjin-cha.

The essential purpose of bunjin-cha is to turn the guest’s awareness outward to appreciate the beauty of the place where the ceremony is being held, rather than to draw it inward as in wabi-cha.

A special moment was enjoyed with sencha made and served using a Mokubei teapot and teacup. Tsukuda complimented the beautiful Mokubei Kochi-yaki pottery. It was so easy to brew the tea correctly, too!

—-In Tea and the Japanese, it is said that bunjin-cha is tea for self-enlightenment, whereas wabi-cha is tea for hospitality.

Tsukuda :

To properly entertain others, you must first find enjoyment yourself. However, in modern Japanese hospitality culture, the general consensus is that we must follow the kata, the established movements and etiquette as taught by our teacher, similar to the way we would follow a manual.

The basic concept of bunjin-cha contradicts that notion. It instead hinges on the idea that tea is slowly brewed for oneself, not for others. Originally, bureaucrats and people of culture brewed tea for themselves in their studies, where they would draw or appreciate pictures, read their works, or write by themselves. While engaging in these activities, they would brew more tea and continue to enjoy it alone. That is the origin of this unique tea culture.

Then, a friend might happen to visit and say, “Well, let’s talk together, and I’ll make you a cup of tea while we’re at it.” That’s all there is to it. We can enjoy ourselves and simply share that enjoyment with others. That is the ultimate hospitality, don’t you think?

The tea leaves are measured by pouring them from a chatsubo (tea jar) onto a chago decorated with Mokubei artwork. The chago is a tea utensil used to measure the amount of tea, and for sencha, it is made of split bamboo. This Mokubei chago is folded in two like a book, adding an element of playfulness to the process.

—Forget hospitality just for the sake of hospitality—you want authentic hospitality that you and I can truly enjoy.

Tsukuda :

That’s right. But what is impressive is that we do not argue or fight. Even if we have different opinions about a work of art, we are merely interested in noting those differences. It is encouraging that we, as intelligent people, can calmly appreciate the differences in one another’s position on a matter.

Mokubei dyed brush and teapot. The brush has special symbolism in bunjin-cha.

Literally meaning a “literary gathering” in English, bunjin-cha could be likened to a kind of literary or artistic society. Except that this literary gathering, which includes tea, is all about noticing and appreciating what makes each of us different.

—Can non-Japanese people experience the real Japan through bunjin-cha?

Tsukuda :

In order to appreciate our differences, we need to improve our cultural awareness by discussing literature and art together. This was once done in Europe over coffee and wine, so in that sense it is a global practice.

Selection of sencha utensils by Mokubei. Clockwise from top right: A teapot on a brazier, a teapot on a stand, a feather broom for cleaning the brazier and its surroundings, a water jar, a tea bowl, and a jar for tea leaves.

For example, I had the opportunity to conduct a bunjin-cha session for a partner program during the G20 summit in Osaka in 2019. The attendees probably thought it was going to be a typical formal tea ceremony, but as soon as it started, they realized that it wasn’t.

Then, Sir Philip (the husband of then British prime minister Theresa May) spontaneously suggested that everybody write a poem, and Ivanka (daughter of then US president Donald Trump) said, “I’ve already written a poem!” We were able to use the time while the tea leaves were gently brewing to relax, unwind, and compare our cultures, regardless of age, title, or where we came from—the East or the West.

It is not enough for people to spend their lives working 365 days a year. Long ago, bunjin-cha began when busy bureaucrats and politicians started taking a break from their work and enjoying themselves with a relaxing cup of tea alone in their studies or together with friends, ignoring status or position. It was a world away from the rigid organizational structures emphasizing success and prestige. Bunjin-cha opens up rich opportunities to discover and explore unfamiliar worlds and different cultures, such as the classics or contemporary art. Don’t you think there is a need today for such opportunities for close communication in Japan and around the world?

Talking is important during bunjin-cha.

People began to enjoy comparing cultures during the Edo period. You could say that this kind of interaction involving Japanese tea is both intellectual and quintessentially Japanese. I think this perspective is contrary to the common impression that Japan has a specific kind of tea ceremony.

—In Tea and the Japanese, the word “exoticism” is used, implying that the Japanese tend to conflate exoticism with Japaneseness.

Tsukuda :

You’re right. And sometimes, when I dive too much into Japan, I suddenly yearn for a taste of different cultures, so I try to travel abroad for a bit. If I don’t do that, I will go crazy. I think that helps me find the best sense of balance. In fact, it is the inclusion of contrasts that makes Japan unique.

The fact is that Japan received tea culture from China but then developed over time the aesthetic of wabi-cha—creating a new tea culture of its own. Therefore, if foreign people were to take away that tea ceremony is unadulterated Japaneseness, you really wouldn’t be seeing the real Japan.

—I would like to participate in bunjin-cha!

Tsukuda :

You are welcome any time! We do not have an iemoto system (a hierarchical system of teaching and certifying a Japanese art form), nor do we have a master-disciple or diploma system like wabi-cha, so you can just enjoy bunjin-cha easily and freely. My colleagues and I lead regular practice sessions in Tokyo, Osaka, Kyoto, and Shiga. It is fun no matter where you join us!

The beautiful open-air teahouse Gencho-an, designed by Kengo Kuma, is on the sixth floor of the Suntory Museum of Art, having been moved here from the former museum. It is a splendid fusion of tradition and modernity.

Those who regularly participate in bunjin-cha include both men and women in about equal numbers. Recently, we have seen a large number of people from the art world, not only creators but also curators, and many people in their forties or fifties. It’s fascinating to see the busiest generation in society relaxing in the world of bunjin-cha, which in turn improves their business skills. I feel that the people who come to bunjin-cha have that kind of industrious energy.

If you think about it, bunjin-cha has always been a gathering place for extraordinary leaders and educated individuals since the Edo period. Such intellectuals were, and still are, most likely true literati.

—Can non-Japanese people join in bunjin-cha?

Tsukuda :

Of course! If we know in advance, we can provide an interpreter. In fact, we have visitors from abroad once a year. In recent years, with the Osaka-Kansai expo coming up, we have received many inquiries from governments and travel agencies, and we are in the process of devising a cultural exchange tour that includes a meal.

Far beyond nationality and title, I find the most enjoyment in discovering a different world within myself. I would be happy if a moment of brewing sencha could help you do so too.

“Bunjin-cha is the exact opposite of hospitality,” says Ikki Tsukuda.

“What I want you to know is that in addition to the tea of perfect form, discipline, and hospitality, there is also the tea of self-enjoyment, emotion, and conversation, and that the two together form the real Japanese tea culture. There is a flexible Japanese way of being that is both the same and different, that includes conflict and harmony, and that comes and goes freely in either direction” (Ikki Tsukuda, Tea and the Japanese).

Ikki Tsukuda was born in Osaka in 1952. He is the head of the Issa-an school, which has passed down the tradition of bunjin-cha tea ceremony from the late Edo period. He is a member of the board of directors of the Society for the Cultural Studies of Chanoyu and a member of the advisory board of the University of Tokyo Humanities Center. His books include Sencha-no-Tabi: Bunjin-no-Tokoromi, Nine Secrets of Delicious Tea, and Tea and the Japanese.