“Thwap!” is the sound of 300 kg of naked human flesh colliding, as two human behemoths square off, and it marks the beginning of a sumo match. Don’t blink, the action may be over in less than a minute or it may last a bit longer, but only until one sumo either topples to the clay or is pushed out of the ring. There is no clock. There are no points. It’s win or lose.

Japan’s ancient sport of sumo has remained largely unchanged for more than 400 years. The rules are simple, the action is brutal, and the wrestlers are humble. That’s what makes it so fascinating to foreigners and travelers visiting Japan.

Today, as Covid-19 fades into the background, sumo is rising in popularity. Fans, tourists, celebrities, and casual observers are flocking to the six tournaments held every year. Often matches are sold out. Every year three tournaments are held in Tokyo (January, May, and September) and one each in Osaka (March), Nagoya (July), and Fukuoka (November). Each tournament lasts 15 days, during which top division wrestlers compete in one bout per day. Prices range between 2,300 to 14,000 yen per ticket.

“When I look at the expressions of tourists and locals in Kokugikan stadium, they all seem to love being there. While the locals may be visiting mainly for the wrestling and socializing, the tourists are witnessing something they would never experience back home. The costumes, ceremonies, atmosphere, and intensity make for top-tier entertainment, even for people who are not usually interested in sports,” says Lord K2.

That’s the pen name of London-born, David Sharabani, who recently published a book titled, Sumo (Ammonite Press, 2022), which features 100 photos of wrestlers in and out of the ring, and offers a rare and intimate look into the secretive world of sumo.

Lord K2, who makes his home in Tokyo, has always had a passion for martial arts. Including the Thai combat sport of muay thai, which he has also captured in photos.

https://www.lordk2.com/sumo-book

“I’m a big fan of Asian combat sports, and the one I enjoy watching most is sumo wrestling. The size of wrestlers, costumes, customs, and rituals make it visually interesting to photograph,” he says.

Sumo Goes Way, Way, Way Back

Sumo began to develop as a professional sport during Japan’s Edo Era, in the 1600s, when wrestlers from around Japan were invited to battle in front of imperial courts. Many wrestlers were samurai working part time for extra cash. The first professional tournament was held in 1648 at Tomioka Hachiman Shrine in Tokyo. The sport became more regulated with the formation of the All-Japan Grand Sumo Association in the 1920s. Today, the organization is called the Nihon Sumo Kyodai Kyokai or simply, in English, the Japan Sumo Association.

“I like that the sport has mostly stayed the same over time. While most sport’s governing bodies have bowed to the pressure of television companies seeking modernization, and appealing to an audience that requires instant stimulation, the Sumo Association has been committed to maintaining the sport’s traditions, and this is a rare phenomenon these days,” he says.

How did Lord K2, who speaks little Japanese, gain access to the inner sanctum of sumo? He certainly took an unlikely path to the dohyo (as the ring is called). A graduate of London’s Middlesex University with a BA in business, he spent most of his early working life trading stocks from his laptop while travelling internationally.

A visit to Buenos Aires unleashed his creative juices. There he initially took to the streets to spray-paint stencils before gravitating toward a new creative outlet: photographing the graffiti artists who were tagging the infrastructure around him. That’s also how he came up with the name Lord K2.

“It was my graffiti tag. I was watching K1 martial arts, and I liked how it sounded. It also refers to a mountain which is a positive thing. Later, I decided that I wanted a unique name, so I added the ‘Lord’ bit. In South America, I was perceived as somewhat Lord-like due to my clean-cut appearance, lifestyle, and accent,” he says.

From Graffiti to Photography

Eventually, his passion for photography converged with his love of martial arts. He traveled to Thailand, where he was granted access to all areas of the Muay Thai industry, leading to two photobooks on the sport. Next, he came to Japan and somehow managed the amazing feat of gaining an all-access pass to Tokyo’s Kokugikan Stadium, where sumo tournaments are held. However, it took a lot of patience to make it.

“It was a significant challenge to gain access,” he says. “Initially, I was refused by everyone associated with the sport. There is a rigid system in place for determining which photographers may be permitted to shoot, and I was not a part of that system, nor could I speak Japanese.”

However, he did not give up. He eventually made some good connections, and after a year of trial and error and near soul-crushing frustration he was able to persuade the Sumo Association that, as he puts it, his. “…style of photography lent itself to taking attractive photos of sumo and portraying the sport in a positive light that would generate positive publicity for the sport.”

“I wanted to piece together a series of photographs for a global audience, who generally know very little about sumo, offer them an insight, and inspire them to visit Japan to watch sumo, or even take up photography,” he says.

The Calm Before the Storm

At the beginning of a sumo match there’s a slight buzz in the arena as the wrestlers emerge and make their way to the dohyo. The dohyo is a raised mound of clay, which has been purified by a Shinto priest. It’s demarked by marked by a circle of bundled rice straw and sits well above the heads of the nearest fans. At the beginning of each bout, the wrestlers step into the ring, grab a handful of salt and toss it to the side to banish evil spirits. At first, the loudest voice in the arena is the referee who calls on the men to face off.

The combatants squat less than a meter apart and engage in a tense stare down. Once, twice three times they do this looking as if they are a hair trigger from springing at each other like guided missiles, only to stand, part and tromp slowly back to their corners for a quick towel off, and sometimes another fistful of salt to toss into the air. Finally, the referee gets them into their final stance.

There’s a pause. He yells. They burst into action and impact. Then the fans begin to shout, but it’s usually over in the blink of an eye.

Sometimes the loser goes belly-flopping into the front row like a misguided walrus. There are occasions when the results are not to the fans’ liking and scores of thin seat cushions are tossed like Frisbees toward the ring, many of them pelting the spectators in the expensive seats. However, in recent years, Covid-19 rules have put a stop to the more exuberant displays of fandom.

Being allowed to take the photos of sumo is one thing, but getting approval to publish them is another story. To earn approval to publish a photo Lord K2 had to hire a Japanese lawyer to prepare a special release form. Then the form, along with the image, had to be faxed to the Sumo Association. If the photo is approved, the Association would fax back a stamped approval form. That process was required for every single photo in the book. Therefore, it’s no surprise that the project took seven years to complete.

A Look Behind the Curtain

Not only did Lord K2 gain access to the national stadium, but also to the stables where the wrestlers train. Inside the stables there is a strict hierarchy. The higher ranked wrestlers enjoy all the perks, while the novices take care of the stables, and serve their seniors. The stables also house the referees, ushers, and hairdressers. There are 43 stables in Japan where several hundred sumo wrestlers practice and hone their skills.

“Before I visited a sumo stable, I didn’t know what to expect, but I quickly gained respect for the wrestlers. They train hard. They may not look it on the surface, but they are incredibly fit and flexible,” says Lord K2.

At the stables, drills for new recruits start at 5:00 a.m., while the seniors rise at 7:00. The wrestlers begin with a series of stretches, followed by sparing in the dohyo to build endurance and sharpen their technical skills. The stable master sits and watches, occasionally barking orders and offering advice. Later they lift weights and do other workouts. The seniors guide and sometimes haze the recruits, then, training winds down with stretching.

According to Lord K2, the training can be very rigorous to the point of wrestlers screaming in agony as they push themselves beyond their perceived mental and physical limits.

“It’s fascinating how much attention is paid to the hairstyle and dress codes of sumo wrestlers, and also their conduct in the stables and in public,” he says.

No Casual Fridays

Active wrestlers live by a strict code of conduct both inside and outside the ring. They can be spotted dressed in traditional kimono riding local trains or cycling around Tokyo, as they are forbidden from driving cars or wearing contemporary clothes. Rules also dictate that wrestlers must be always soft-spoken and self-effacing. You can be sure there’s no trash talking in sumo.

What do Sumo Wear?

They are not totally naked. The heavy-duty loincloth that makes sumo wrestlers stand out among modern athletes is called a mawashi. Black is worn by wrestlers in the lower divisions. Wrestlers in the top two divisions wear a white mawashi during training, and silk loincloth in a wide range of colors while competing. Wrestlers in the two lowest divisions must wear a yukata (a casual kimono-type robe), and geta (traditional wooden sandals), at all times in public.

There are several factors Lord K2 likes about sumo and the way it’s run. He notes that the wrestlers are allowed up to 4 minutes of preparation time between bouts, which, while slowing down the pace of a match, gives them ample time to prepare and bring out their best. He believes this pace provides a higher quality of wrestling.

Also, unlike Western boxing, there are no weight restrictions or classes in sumo. Wrestlers can easily find themselves matched off against someone many times their size, which adds an element of intrigue to match strategies. No doubt, weight gain is an essential part of sumo training. And most importantly, there is only one champion at a time.

What do Sumo Eat?

Well, everything, but one dish is very important; chankonabe can be described as the Japanese version of Irish stew. It consists of beef, pork, chicken, fish, and vegetables. Recipes are secretly guarded, and each stable has its own variation. It’s served with rice on the side. Lots of rice. It’s all washed down with plenty of beer and sake. Yes, sumo wrestlers are allowed to drink alcohol.

Ordinary folks can sample chankonabe at Tokyo restaurants located near sumo stables.

“I was surprised by how much fun sumo wrestlers can be outside of training. As well as being approachable, they are often jovial and playful. This kind of contradicts their intimidating demeanor, as the guys are true warriors.” says Lord K2.

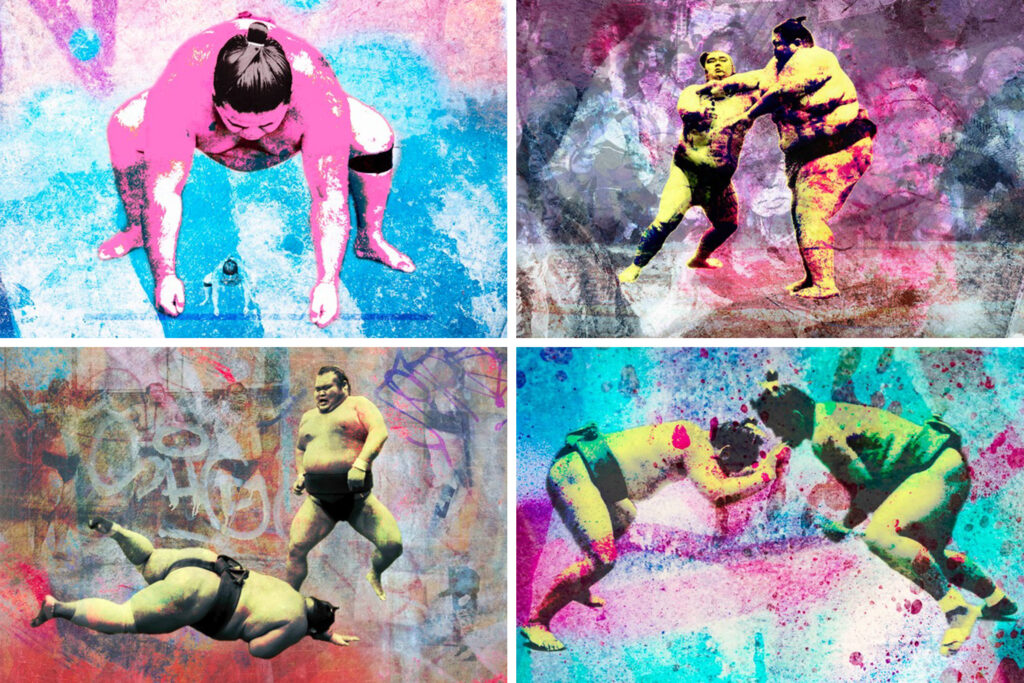

Currently, he is working on a new project of paintings using his sumo photos as the foundation. He employs acrylic paint to combine colors, words, and graphics with photos to create original artwork. The style is somewhat reminiscent of Andy Warhol’s later work with celebrity and news photos. He intends to have an exhibition in Tokyo in the near future. Stay tuned.

https://www.lordk2.com/sumo-art-collection

Lord K2(David Sharabani)

Photograper Lord K2 (aka David Sharabani) also specializes in stencil graffiti and it was from his time in that world that he takes his nom-de-guerre.He has also photographed for the World Muay Thai Council and for the International Federation of Muay Thai Amateur.

His work has been featured on the front cover of Asian Geographic, as well as in numerous online and offline news media.

In addition to documenting his sports, Lord K2 photographs urban art, and he is author of the highly acclaimed Street Art Santiago (Schiffer,2015), Tokyo Graffiti (Schiffer, 2018), Street Art Tel Aviv (Sussex Academic Press, 2021) and Street Art NYC (Dokument Press, 2022). He is currently based in Toyko.

◾️ Ready to dive into the world of sumo?

Experience the Power of Sumo: Private Guided Morning Practice Tour and Learn About Japan’s National Sport

Price:from ¥26,000 /person

Time:90mins

Location:Tokyo

Observe Sumo Training at a Sumo Stable in Ryogoku, Tokyo – with Expert Commentary and Souvenir

Price:from ¥40,000 /person

Time:130mins

Location:Tokyo