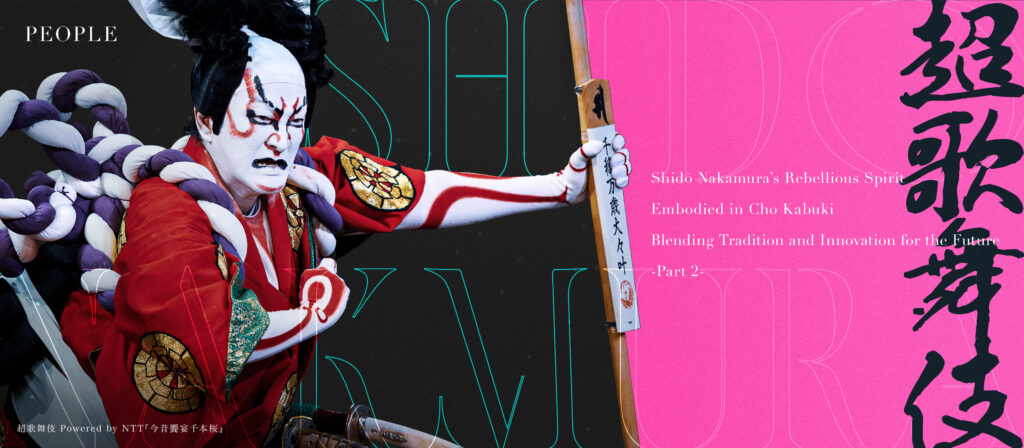

Kabuki actor Shidō Nakamura is a man of many talents. When he’s not gracing the Kabuki stage, he’s a fixture in TV dramas, movies, and other productions. In December, the iconic Kabukiza Theater will present Cho Kabuki, which Shidō has been working on since 2016. The show, which ingeniously blends classical Kabuki with cutting-edge technology, features a collaboration with virtual singer Hatsune Miku that has garnered considerable attention. At last, the culmination of Nakamura’s creative efforts will come together to captivate audiences on a grand scale.

Cho Kabuki receives fervent support not only from Kabuki enthusiasts but also from Hatsune Miku fans. One captivating aspect of the show is the climax, where Shidō, dressed as the character Kitsune Tadanobu, energetically engages the audience in a style reminiscent of a live-music club. Here, we explore how he became involved in Kabuki and what his aspirations are, as well as what fuels Shidō’s energetic and ambitious pursuits beyond his groundbreaking performances.

Shidō: I consider Cho Kabuki to be a mission entrusted to me. Among Kabuki actors, there are those who focus solely on classical Kabuki, while others, like me, venture into new Kabuki and unprecedented genres. I think that having different types of actors is a wonderful thing, and I personally felt that in order to secure roles, I had to challenge myself by pushing the boundaries of what was possible.

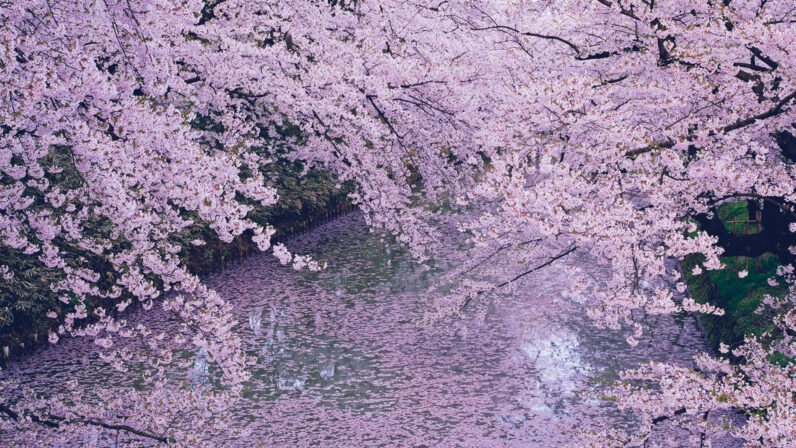

An example of a new genre is Cho Kabuki, which taps into otaku culture. I used to perceive otaku as having a different mindset, but upon careful analysis, I realized that they possess an energy that is changing the times. This energy has not only given birth to virtual singers but has propelled them into a global phenomenon. Having witnessed the extraordinary energy when otaku, who can be passionately devoted to one thing, come together, I was curious to see how the otaku community would react when classical Kabuki merged with Hatsune Miku in Cho Kabuki. Fortunately, classical Kabuki fans and otaku have found common ground over time with repeated performances. It’s profoundly moving to know that my desire to make Cho Kabuki a genre all its own will be realized in December when the show premieres at the Kabukiza Theater.

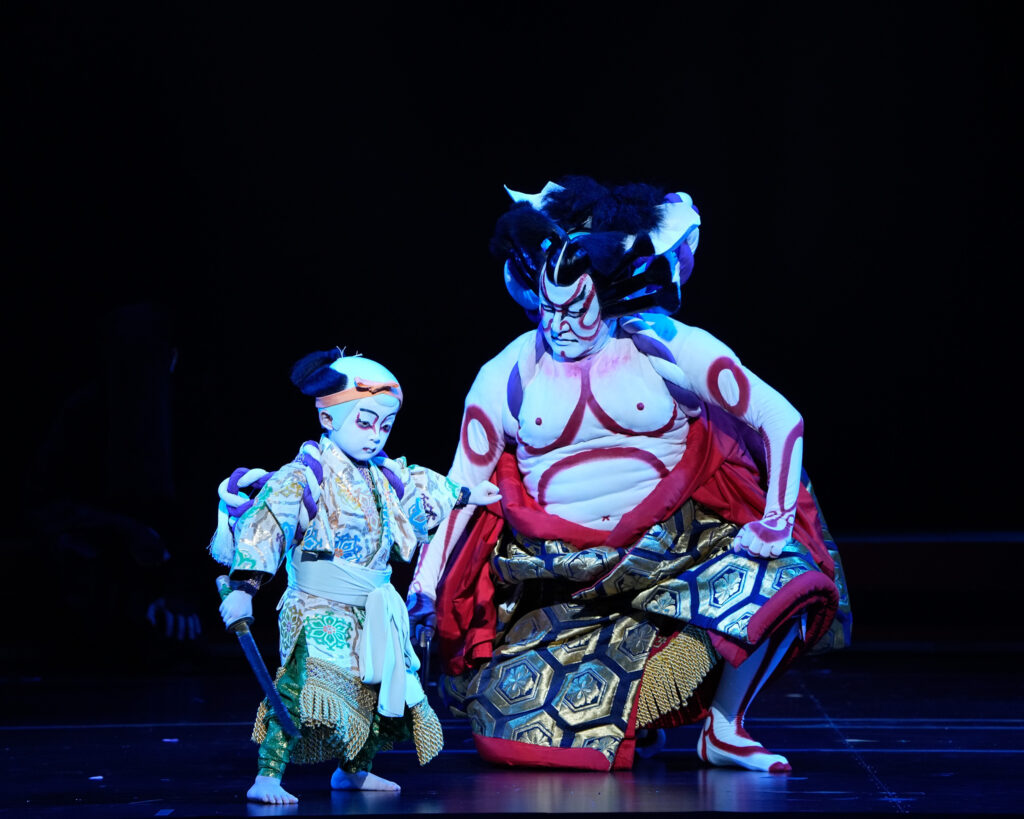

HANAKURABE SENBONZAKURA (August 2019, Minamiza Theater) ©Shochiku & NTT / ©Cho Kabuki

An example of a new genre is Cho Kabuki, which taps into otaku culture. I used to perceive otaku as having a different mindset, but upon careful analysis, I realized that they possess an energy that is changing the times. This energy has not only given birth to virtual singers but has propelled them into a global phenomenon. Having witnessed the extraordinary energy when otaku, who can be passionately devoted to one thing, come together, I was curious to see how the otaku community would react when classical Kabuki merged with Hatsune Miku in Cho Kabuki. Fortunately, classical Kabuki fans and otaku have found common ground over time with repeated performances. It’s profoundly moving to know that my desire to make Cho Kabuki a genre all its own will be realized in December when the show premieres at the Kabukiza Theater.

From left: Haruki Ogawa, Shidō Nakamura

TOWA NO HANA HOMARE NO ISAOSHI (September 2023, Minamiza Theater) ©Cho Kabuki 2022 Powered by NTT

—Following in the footsteps of your first son, Haruki, your second son, Natsuki, will be performing on stage in this show. How do you feel about that?

Shidō: In the world of Kabuki, even brothers become rivals. I thought it’d be cool if Natsuki wanted to become a rock star or hip-hop artist, but surprisingly, he said of his own accord, “It’s unfair that Haruki gets to do it. I want to do it too.” Even before he had any formal training, he was eager to dress up in kimono and perform short and humorous improvised skits.

But they’ve been lucky enough to have a lot of experiences that I never had as a kid, so I’m pretty envious, you know [laughs]. When they put Haruki on stage for his debut performance, they had him wear traditional kumadori (stage makeup), perform tachimawari (sword-fighting scenes), and do a stylized form of walking known as roppo as he retreated from the stage on the hanamichi (a long, raised platform that runs from the back of the theatre to stage right at the level of the audience). They incorporated everything Haruki liked. When I was little, there were hardly any new Kabuki plays like Cho Kabuki, so there were no roles where child actors could wear traditional stage makeup. I had only low-key roles, like that of a young servant who had a shaved head or wore a bobbed wig. I aspired to be a Kabuki actor and imagined a future in which I would grow up, put on stage makeup, participate in sword-fighting scenes swinging a magnificent sword, and striking powerful emotional poses known as mie. Since my sons were able to do such things from the start, the future might be challenging for them in a different way.

Natsuki may one day say, “Man, I’ve gotta dive into hip-hop” [laughs]. I hope they can freely follow their own dreams without worrying too much about parental expectations or societal norms.

Left:Haruki Ogawa, Right:Natsuki Ogawa, Center:Shidō Nakamura

—What drew you to Kabuki when you were a child?

Shidō : In everyday life, we never see people with pure-white faces, so when I saw a Kabuki performance as a child, I was surprised. I guess it was the kumadori and the dramatic tachimawari that impressed me. At that time, it was rare for Kabuki to be filmed, so seeing live performances made me want to try my hand at this traditional form of Japanese theater.

The Kabuki plays by Ichikawa En’ō II, a prominent member of the Omodakaya guild, made an especially lasting impression on me. In particular, the ‘shi no kiri‘ (fourth act) of Yoshitsune Senbon Zakura featured quick costume changes known as hayagawari and flamboyant, acrobatic performances such as chūnori, in which actors fly through the air suspended from a wire. As I watched from my seat on the second floor, I was mesmerized. Even as a child, I felt the grandeur of it all and found it interesting, thinking that I would like to perform in that way too. Children are attracted to such extravagant performances, known as kerenmi, and I myself once tried to perform such aerial movements at home. I wrapped a rope around my body, hooked it to a dresser, and had my mother pull me up. Well, the hook broke, and it was quite a scene [laughs].

Now, when my two sons come home, they start play fighting in improvised skits. Watching them, I realize that I used to do the same thing. I think Kabuki appeals to children not through logic but by capturing their hearts because it’s cool and aspirational. In Kabuki, there’s a type of posturing called mie. I suppose that wanting to strike such poses is similar to wanting to be a superhero.

Part 1 IWAU HARU GENROKU HANAMI ODORI Yakko Yoshizo : Haruki Ogawa

©Shochiku

—You’re very active, not only in Cho Kabuki but also in fields of acting, music, and others. Where does this energy come from?

Shidō : I think it’s because I want to touch the hearts of those who’re apathetic when it comes to Kabuki. Whenever I perform at the Minamiza Theater in Kyoto, I make it a point during the run of the show to hold a special performance exclusively for students. Before attending this performance, many of the students seem to show little interest in Kabuki. However, when we premiered a new Kabuki play based on the picture book Arashi no Yoru ni (Stormy night), the audience’s response was explosive. The young audience was lively and enthusiastic and even demanded an encore. Seeing how well it was received by the younger audience, I thought that it might be accepted elsewhere. As expected, the reviews were positive, and we were able to perform the play again at the Kabukiza Theater in Tokyo and the Hakataza Theater in Fukuoka.

However, things changed completely with the onset of the COVID-19 pandemic. Those who were about to reach adolescence at that time saw events such as athletic meets, school festivals, and school trips—events that had always been taken for granted—canceled one by one. So, our experience of the pandemic is very different from that of the students. We have become adults by experiencing different things, traveling here and there to enjoy what we want to see or hear. But these students will reach adulthood without having experienced any of that. That’s why, when a socially awkward person newly joins a given community , even though we feel the urge to preach, we should tell ourselves to slow down. So when I think of the audience members who may not have had the opportunity to experience much, I want to touch their hearts and eventually make even those who are traditional Kabuki enthusiasts but resistant to Cho Kabuki stand up in excitement at the end of the show. I go on the stage with that in mind. It’s really a manifestation of my rebellious spirit. Otherwise, I don’t think it would make sense to do this kind of show at the Kabukiza Theater.

—In the Edo period (1603–1867), Kabuki, which was a popular form of entertainment, gradually came to be regarded by many people as an exclusive form of theater. The Cho Kabuki that you’re trying to popularize seems to offer an opportunity to experience the enthusiasm of watching Kabuki just like people did in the Edo period. In your pursuit of tradition and innovation, what are you mindful of?

Shidō : Kabuki always incorporates new elements that are relevant to the times. Some people don’t know this and seem to think that Kabuki is just carrying on old traditions and performing them over and over again, but that approach would lead to its decline. When the actress Shinobu Terajima appeared in ‘Bunshichi Mottoi Monogatari’ at the Kabukiza Theater in October 2023, some media outlets reported that it was a historical achievement for a woman to appear in a show at the theater. But although this may have been a first in the current Kabukiza Theater (fifth iteration), actresses, such as Takako Matsu, have previously appeared in ‘Bunshichi Mottoi’ as Ohisa, the daughter. There have also been experimental performances in the past, with Onoe Shoroku II of the Kioicho guild co-starring with an actress.

Incorporating positive elements from other genres into Kabuki plays is a tradition that dates back to the Edo period. The genre known as Matsubame-mono incorporates interesting aspects of Noh and Kyogen. The plays also include witty jokes and gags that were popular in the Edo period, which may have been uproarious at the time but might not evoke the same reaction from today’s audiences. From this point of view, I believe that if virtual singers had existed in the Edo period, they would have been incorporated seamlessly.

On the other hand, we Kabuki actors have also discussed performing masterpieces that depict the soul of the Japanese people, such as Kanadehon Chūshingura, which is considered one of the three great Kabuki plays. There have been instances of uncut full-length Kabuki performances being staged with all-star casts, drawing large audiences to the theater. While expectations change with the times, I believe that both tradition and innovation are essential to passing Kabuki on to future generations.

Natsuki Ogawa

—From your point of view, what are the interesting or attractive aspects of Japan that we should be promoting to a global audience?

Shidō : Traditional Japanese culture is not only part of the Japanese identity but also something we should exhibit to the world. This applies to the traditional performing arts I’m involved in as well as traditional crafts. People abroad are often interested in and attracted to cultures different from their own. When I visit foreign countries, such as the United States, for my film work, I’m always asked about Kabuki and Noh. As we travel around the world, I think we need to appreciate Japanese culture and traditions more. While Japanese youth are adept at adopting foreign concepts, there aren’t many people who can answer questions about their own country’s traditions and culture when asked by people from abroad. As we enter a global era in which distances between countries are rapidly shrinking, now may be the time to reevaluate our own traditions and culture so that we can share them with the world.

—As a Kabuki actor and father, what message would you like to convey to your children to prepare them for the future?

Shidō : Instead of leaving them something material, I want to share my philosophy of life with my two boys—namely, how I have lived and how I plan to navigate the world in the future—so that when I’m gone, they will know how I approached life. The thoughts I have shared through visual recordings and interviews like this one are now preserved in a tangible form. It’s up to my boys how they interpret and embrace these ideas, but I hope they understand my philosophy of life.

The Fifth Kabukiza Theater 10th Anniversary

December Program

Website : https://www.Kabukiweb.net/theatres/Kabukiza/Kabukiza_december_2023/

Profile

Shidō Nakamura

In 1981, Mikihiro Ogawa made his Kabuki debut at the Kabukiza Theater in the role of the daughter of a tofu vendor in the “Goten” scene in ‘Imoseyama Onna Teikin‘, adopting the name Shidō Nakamura II. In 2002, while working as a Kabuki actor, he gained recognition when he won the Blue Ribbon Award and the Japan Academy Film Prize for Newcomer of the Year for his role as the dragon in ‘Ping Pong’, his first film role. He has since appeared in a number of high-profile TV dramas and films. In 2015, he won acclaim for the Kabuki adaptation of the children’s picture book ‘Arashi no Yoru ni ‘(Stormy night), performed at Kyoto’s Minamiza Theater, and has appeared in subsequent reruns. In 2016, he unveiled the Cho Kabuki play ”Hanakurabe Senbonzakura‘, a collaboration with the virtual singing sensation Hatsune Miku. The play has been performed numerous times, including as part of a highly anticipated nationwide (four-city) tour in 2022. In 2018, he presented a new rendition of the classical Kabuki play ‘Onna Goroshi Abura no Jigoku’ as an off-theater Kabuki performance, staged in warehouses and live-music clubs.

Haruki Ogawa

The eldest son of Shidō Nakamura, Haruki Ogawa made his debut in ‘Iwau Haru Genroku Hanami Odori’ at the Kabukiza Theater in January 2022.

Natsuki Ogawa

The second son of Shidō Nakamura, Natsuki Ogawa made his debut in ‘Hanakurabe Senbonzakura’ at the Kabukiza Theater in December 2023.

■Related Article

Shidō Nakamura’s Rebellious Spirit Embodied in Cho Kabuki: Blending Tradition and Innovation for the Future -Part 2-