Photo provided by Toshifumi Orikami.

Buddhist sculptors are known in Japanese as ‘仏師 busshi.’ One of them is the Toshifumi Orikami, who uses traditional techniques to create, repair, and restore Buddhist statues from his old house in Nara. In addition to his work, he also holds workshops, teaching the art of Buddhist sculpture to the public. When I decided to visit Nara, he was someone I had hoped to meet.

“When I was in college, I read a book by Kyoto busshi Hourin Matsusita, which solidified my decision to pursue this path. I used his book as a textbook while challenging myself to sculpt Buddhist statues, and eventually, I was fortunate enough to become an apprentice under Koushou Yano, a disciple of Matsuhisa.”

When asked about his journey to becoming a busshi, Orikami shared this story. On the day we visited for our interview, he was restoring five Buddhist statues housed in the five-story pagoda of Murouji Temple. Located in a serene mountain area on the border of Nara and Mie Prefectures, Murouji is surrounded by cedar trees that are over 600 years old. The five-story pagoda is Japan’s second oldest outdoor pagoda, built in the 8th century, and is a precious national treasure. However, in 1998, a massive tree struck the roof during a typhoon, causing significant damage. Renovation work in 2000 restored its beautiful cypress bark roof and vibrant red lacquered exterior.

Interestingly, Muro-ji was established before both Mount Hiei and Mount Koya, making it the first mountain temple in Japan. It was highly regarded as a Shingon Esoteric Buddhist training center. Unlike Mount Koya, which prohibited women, Muro-ji welcomed female worshippers, earning it the nickname ‘Nyoninn Kouya’ (Women’s Koya). Even today, many visitors to the temple are women. Some even refer to the five-story pagoda as a ‘heavenly maiden’ because of its petite yet elegant and dignified appearance.

A Dainichi Nyorai sculpture in progress

Even in Nara Prefecture, which is home to numerous temples, there are only about ten artisans actively working as busshi, and most of them specialize in repairs.

“I do repairs, but I also take on commissions from individuals and temples to create new statues,” Orikami explains.

People might ask him to craft a statue for their home altar or as a decorative art piece. He even recalled a time when a foreign visitor bought a scale model of a Nio statue he was working on right then and there. The Dainichi(great sun) Nyorai he’s currently carving has been in progress for about a month, using the finest Kiso hinoki wood.

“The Nio (kongou-rikishi) statue I made before was very large and took nearly two full years to complete. Statues of that size are typically not made by just one person, so I often wondered if I would ever finish it,” he laughs.

He sometimes works more than ten hours a day, and even with that dedication, completing a piece in two years requires an extraordinary amount of mental strength.

Photo provided by Toshifumi Orikami

The Workshop Experience

In this workshop, we carved small Jizo statues. Formally known as Jizo Bosatsu, Jizo is a type of bodhisattva who holds a high rank, second only to Shakyamuni, the enlightened one. In Japan, he is widely revered as a popular Buddhist figure, believed to save people while pursuing enlightenment through practice.

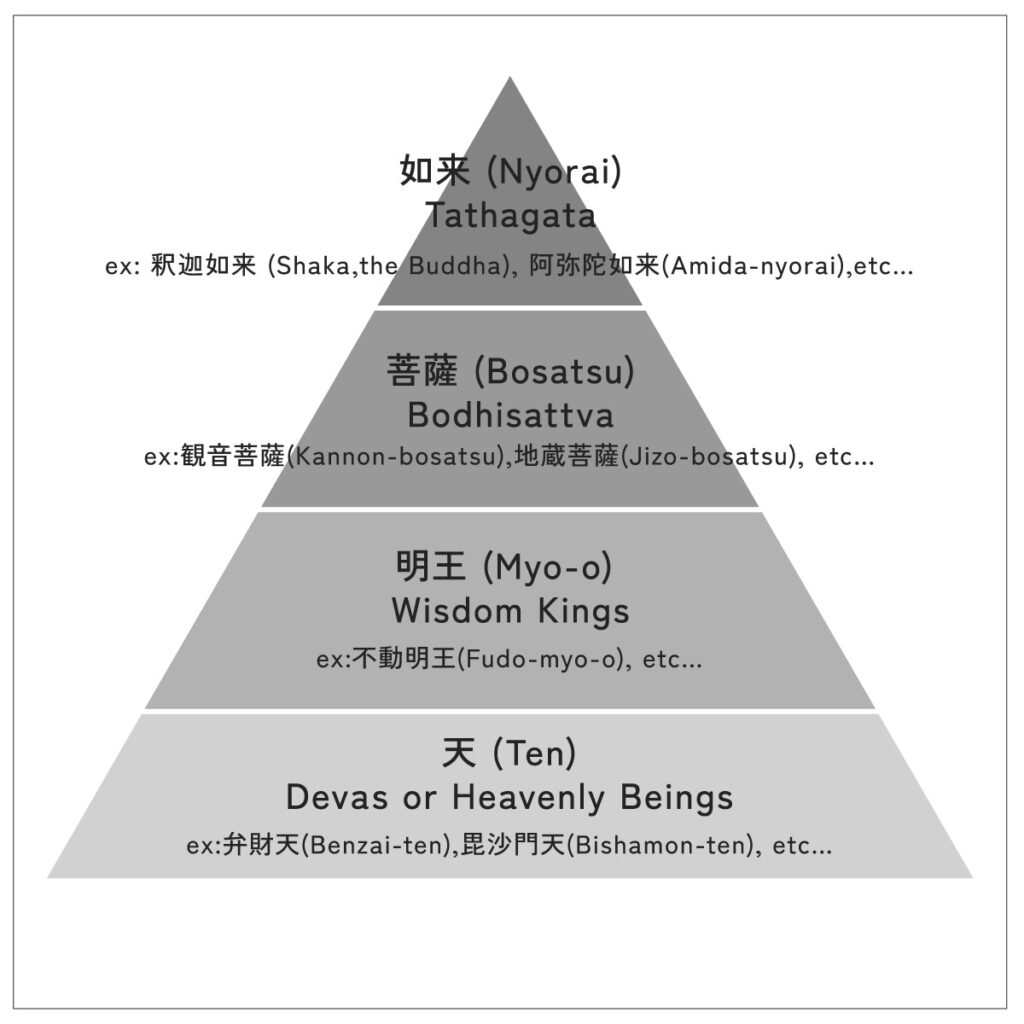

One of the challenges in sculpting Buddhist statues is that they come with various names and classifications. Simply put, they can be broadly categorized into four levels based on their degree of enlightenment. At the top are the Nyorai (like Shakyamuni), who have attained enlightenment. Next are the Bosatsu, who are training to reach that state. Then there are the Myo-o, who protect others and correct those who stray from the path. Finally, there are the guardian deities, whose names often end with ‘Ten’ (meaning ‘heaven’). This four-tiered structure forms the foundation of Buddhist iconography.

Now, back to the workshop. When it began, I was given a small piece of wood with faint guidelines drawn on it. It had a lovely aroma. I wondered whether my instinct to smell the wood came from knowing that it had a pleasant scent or if it was just a primal instinct… As I pondered this, Orikami informed me that it was Kiso hinoki wood.

As I received careful instruction on how to hold the carving tools, I gradually and cautiously began to carve. The wood has two grain patterns: the straight grain (narai-me), which follows the fibers, and the cross grain (saka-me), which goes against them. Carving against the grain can cause the wood to break or splinter, so it’s important to carve in a consistent direction that follows the grain. When I did this, the blade glided smoothly with a satisfying feel. I couldn’t help but exclaim, “This is so easy to carve!”

Orikami chuckled with a hint of pride and replied, “Kiso hinoki is by far the highest quality among domestic hinoki, making it easy to work with. It’s like the fatty part of tuna, the otoro!”

With the tension of handling sharp tools, my focus sharpened at my fingertips. It’s not often that I concentrate this deeply on something, and I found myself lost in the moment. Orikami mentioned that when he carves Buddhist statues, he enters a mindful state.

“I once thought about trying meditation, so I went to experience zazen. I realized, ‘Wait, this feels just like what I usually do.’ People often say meditation is about focusing on your breath, but when I’m working like this, I feel like I’m always in that state.”

As I searched for the image of the Buddha within the piece of wood, I quietly carved out the vision in my mind. Carving Buddhist statues may very well be a form of practice in itself.

Photo provided by Toshifumi Orikami

Appreciating The Art of Buddhist Statues

Buddhism originated in India around the 6th century BCE and gradually spread throughout Asia over several centuries. As it integrated the customs, cultures, and values of various regions, it evolved. About 500 years after the Buddha’s passing, ‘Mahayana Buddhism’ emerged, offering a reinterpretation that made the teachings more accessible to the general public compared to early Buddhism, which focused strictly on enlightenment. The form of Mahayana Buddhism that arrived in Japan around the 6th century came via China.

Later, in the 8th to 9th centuries, the monks Saicho and Kukai traveled to China and returned with ’Esoteric Buddhism,’ founding the Tendai and Shingon schools, respectively. This significantly advanced the development of Japanese Buddhism. Esoteric Buddhism introduced a variety of Buddhas, leading to a substantial increase in the types of Buddhist statues.

“For instance, Dainichi Nyorai is regarded as the center of the universe in Esoteric Buddhism. Typically, as one progresses through the stages of enlightenment, the adornments become more understated. However, Dainichi Nyorai is often depicted wearing a crown and luxurious regalia, indicating his unique status among the Buddhas.”

Buddhism has ritual regulations known as ‘giki,’ which dictate certain design elements for the statues central to these rituals. For instance, the ‘Thirty Two distinctive marks and Eighty characteristics’ outline the physical characteristics of the Buddha. Features like the unique hairstyle found on Buddha statues and the protrusions on the forehead are two of these thirty-two marks.

Additionally, there are specific guidelines regarding proportions, similar to the Golden Ratio, which were established by sculptors from the late Heian period to the early Kamakura period in the 12th century. Speaking of the Kamakura period, two particularly renowned sculptors are Unkei, known for his robust and dynamic statues, and Kaikei, who favored a more delicate and painterly style.

“As beginners, we’re taught to aspire to the Kaikei style,” Orikami explains. “It has the most realistic proportions and makes the most sense. The carving is quite intricate; while many sculptors tend to leave thicker lines to avoid over-carving, Kaikei pushed the limits to create incredibly fine details.” He adds that even with today’s technological advancements, surpassing their masterpieces remains a significant challenge.

Photo provided by Toshifumi Orikami

While admiring the small, palm-sized Jizo Bosatsu I had been carving, I was shown photographs of statues by Unkei and Kaikei, taken by the renowned Buddhist statue photographer Kozo Ogawa. I could only express my amazement at how they managed to create such incredible works of art.

In modern times, many people may relate to Buddhist statues not so much as objects of prayer but as works of art to be appreciated, or even as figures to support like a beloved figure. Just experiencing the process of holding a chisel and carving a piece of wood has brought me closer to the essence of the statue and deepened my respect for the artisans. I’m now looking forward to my next visit and have a new sense of admiration for the statues.

Toshifumi Orikami Buddhist Sculpture Workshop Contact MAIL: tosi_ori@msn.com https://profu.link/u/narabusshi Classes are usually available on a monthly tuition basis, with two sessions per month. For foreign travelers, participation is permitted provided they arrange for an interpreter.

■Related Article

Tranquil Mornings in Nara: Exclusive Experiences at Shisui, a Luxury Collection Hotel, Nara

Nara Hotel: A Classic Establishment with 115 Years of History That Once Welcomed Einstein