Spanning approximately 760 square kilometers across Tokamachi City and Tsunan Town in Niigata Prefecture, the Echigo-Tsumari Art Triennale is seen as the catalyst for Japan’s regional art events.

One of the World’s Largest Open-Air Exhibitions Pioneering Local Art Scenes

The Echigo-Tsumari Art Triennale (ETAT) is regarded as a trailblazer in large-scale, community-driven art festivals.

The concept for ETAT began in 1994 as a means to revitalize the region through art. Under the leadership of Niigata-born art director Fram Kitagawa, the festival held its inaugural event in 2000, drawing approximately 160,000 visitors from July 20 to September 10. Since then, it has continued on a triennial basis, now marking its 25th anniversary. Currently, the festival spans around 90 days and attracts over 500,000 visitors.

Although primarily a triennale, several artworks that incorporate the vast natural landscape of Echigo-Tsumari remain as permanent installations, with ongoing exhibitions in local museums. Additionally, embracing the region’s status as one of Japan’s snowiest areas, the festival now hosts Echigo-Tsumari Art Field Winter 2025, a seasonal event running until March 9. However, even if one misses this winter program, the region offers plenty to enjoy year-round.

Though completely covered in snow, these are terraced rice fields. The artwork in the foreground will be covered later on.

When ZEROMILE’s reporting team visited, it was a warm day right after a heavy snowfall. Many roads were closed, and there were a lot of places that were inaccessible. But even so, it was an amazing time, so much so that the team was completely worn out by the end of the day. While the main ETAT event happens in the summer, there’s something special about taking the time to experience the artwork in the calm, snow-covered landscape. It’s definitely not a bad way to experience it.

Ilya & Emilia Kabakov’s Place Where Dreams Come True

The first stop on our journey was the Matsudai NOHBUTAI, a field museum consisting of a building constructed for the second ETAT in 2003 and the surrounding satoyama landscape.

During the summer, visitors can observe the museum’s unique box-shaped architecture, which sits upon structures like ‘legs.’ However, when the supports are covered in snow, it creates the illusion of floating.

The area features numerous works by world-renowned artists, including Yayoi Kusama’s Tsumari in Bloom. Particularly notable is the collection of works by Ilya & Emilia Kabakov. The U.S.-based artists, originally from the former Soviet Union (present-day Ukraine), have their works displayed together, attracting many visitors who come specifically to see the Kabakovs’ art.

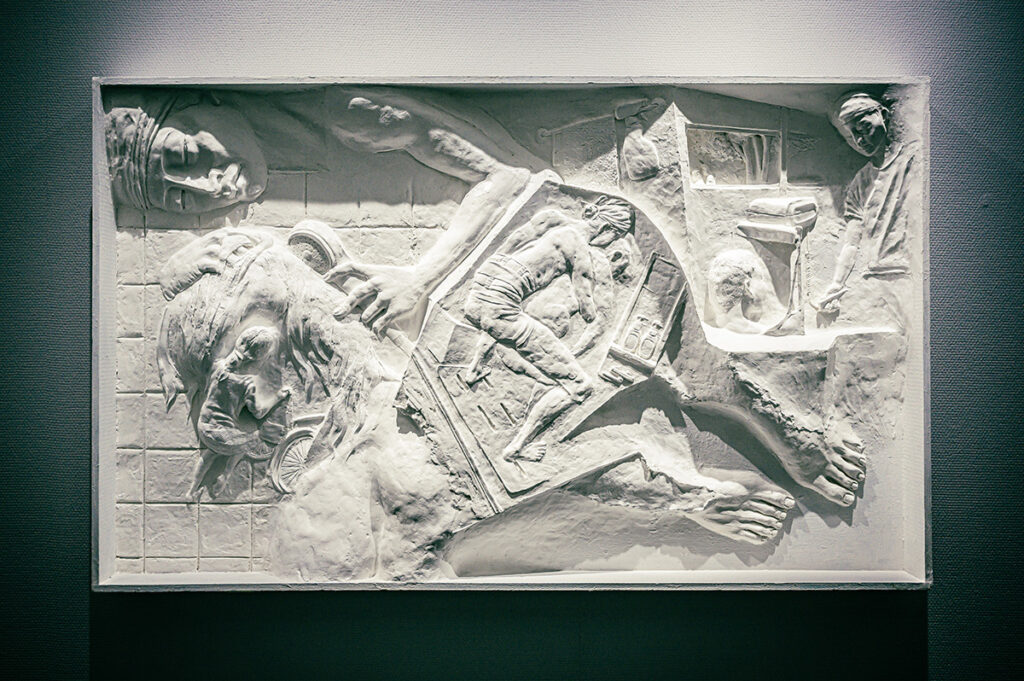

Among their works on display are The Rice Fields, created during the first ETAT, as well as 10 Albums, Labyrinth, The Palace of Projects, and How To Make Yourself Better, all of which are permanently exhibited indoors. Each piece, with its lighthearted humor that makes you chuckle, also conveys profound emotions.

10 Albums, Labyrinth

Ten stories and drawings are displayed in a flowing, curved arrangement throughout the exhibition space, with each centered around a different dreamer.

For example, 10 Albums, Labyrinth unfolds like a picture book, presenting ten different stories. One episode features a character hiding inside a wardrobe. For him, the ‘outside world’ is the interior of the house, but beyond the window lies an even greater world. As the story progresses, details about who this character is and the environment he inhabits gradually come to light, weaving a strange and intriguing narrative.

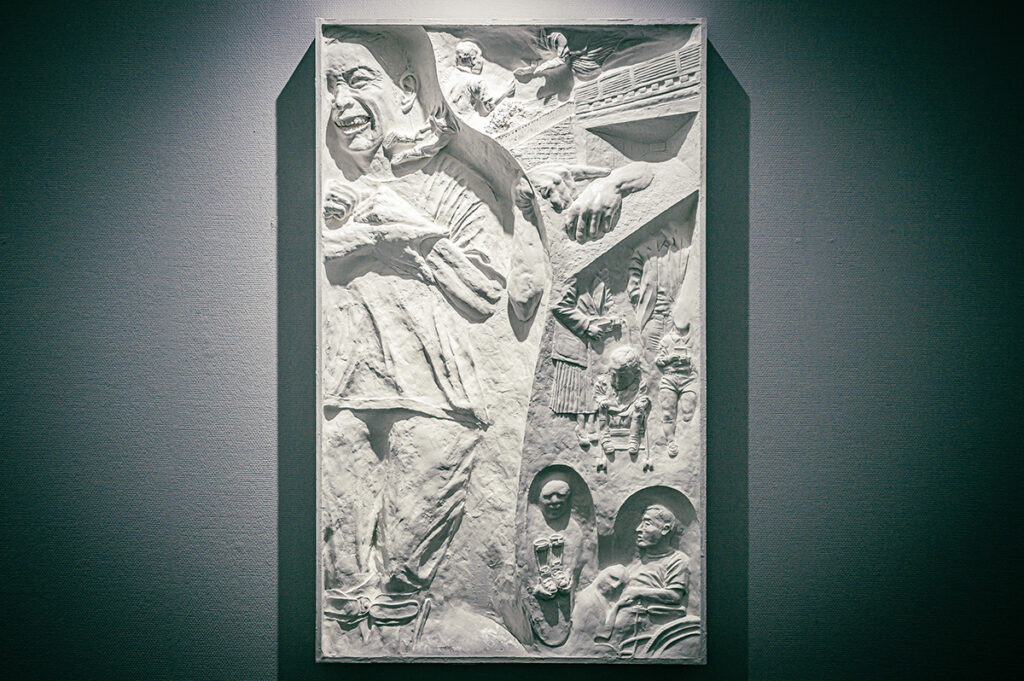

How To Make Yourself Better

As the title suggests, How to Make Yourself Better depicts an experiment in which a person, hoping to improve themselves, sits at a desk wearing a pair of artificial angel wings. The stillness of the snow-covered landscape and the crisp light streaming through the window create an almost dream-like atmosphere. Immersed in this deeply narrative work, it’s easy to lose track of time, and feels like stepping into another world.

The Artist’s Library

A collection of limited-edition artist books by Kabakov and others.

The museum’s library walls feature a message from the Kabakovs, expressing their admiration for the natural beauty and culture of Echigo-Tsumari. Particularly moving are their words: “Our installations in Tsumari are among our most important works” and they even liken the people of the region to “magicians who bring dreams to life.” The message concludes with a powerful reflection: “Culture and beauty will always endure—they are what make us human.” They described this place as a dreamlike setting where that truth can be fully felt.

Snow becomes a dye and eventually a scene by Seki Mirai

Snow as a Medium of the Art

Stepping out from the warmth of the indoors into the vast field, one can’t help but feel the vastness of nature. At the time of our visit, two outdoor artworks were accessible: Takuro Goto’s Snow Country – A House in Obanazawa and A House in Nishine, both oil paintings on wooden panels, and Mirai Seki’s Snow becomes a dye and eventually a scene.

Snow becomes a dye and eventually a scene is a work shaped entirely by nature, inviting viewers to observe how snow gradually accumulates on a network of stretched wires. Located in a relatively open area near the museum, it’s easy to approach. In contrast, Takuro Goto’s pieces sit at the foot of terraced rice fields, along a riverside path, blending more deeply into the landscape.

Step outside the museum, cross the bridge, and follow the path on the left side of the photo. Continue walking until you reach the opposite side of the museum, where you’ll find Takuro Goto’s Snow Country – A House in Obanazawa and A House in Nishine.

While the local tanuki sprint effortlessly down this path, for city dwellers, reaching the site feels like a small adventure. Walking through the snowy landscape at an unhurried pace, you eventually come upon paintings of wooden houses, collapsed under the weight of wind and snow. It’s a moving sight, one that makes you reflect on the bond between the land and the people who call it home.

Takuro Goto’s Snow Country – A House in Obanazawa / A House in Nishine.

The design is undeniably clever, and while we didn’t know who came up with it or how, you could almost believe it was the work of a magician who knows the land inside and out.

The Freedom of Art and the Art of Freedom

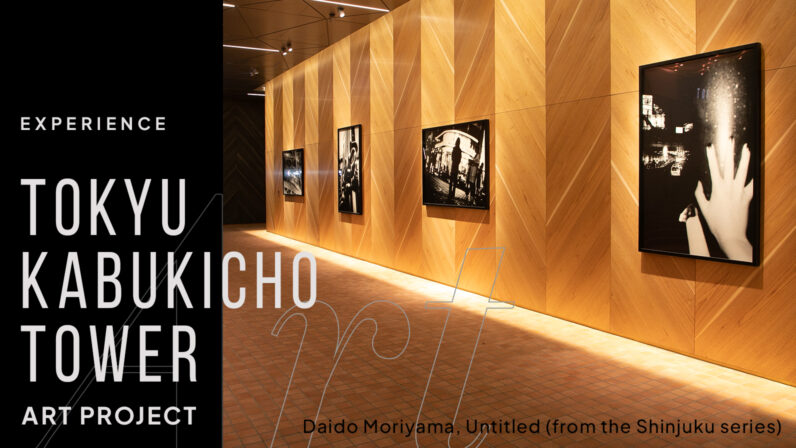

Another notable aspect is the lack of instructions or restrictions around the artworks. This was especially noticeable at the Echigo-Tsumari Satoyama Museum of Contemporary Art MonET, the central museum of ETAT, which we visited after the Matsudai NOHBUTAI.

MonET is a cloister-like building designed by architect Hiroshi Hara, known for his work on Kyoto Station and the Sapporo Dome. In the expansive, open courtyard, the event Voyage of the Great Snowfield with Captain MonET was taking place. The boat in the photo is part of Owa Tatsushi-TAiRiN’s artwork Captain MonET’s Ark.

When you step inside, there’s a lively buzz of people, like you’d hear in a park. It’s probably because the day coincided with the local Snow Festival (which has a long history, dating back to 1950), but this museum is designed for both adults and children to interact with and enjoy the art. It’s unlike any contemporary art museum I’ve been to.

The corridor on the first floor, in particular, has many works that are fun for children to play with (even our team of adults enjoyed them just as much).

After passing through the lively first-floor corridor, filled with both children and adults, we entered the building and were immediately greeted by a special exhibition by Kan Miyake, an artist from Takasaki City in Gunma Prefecture, now based in Tokyo. A workshop led by the artist was also taking place, with his large, colorful works displayed nearby.

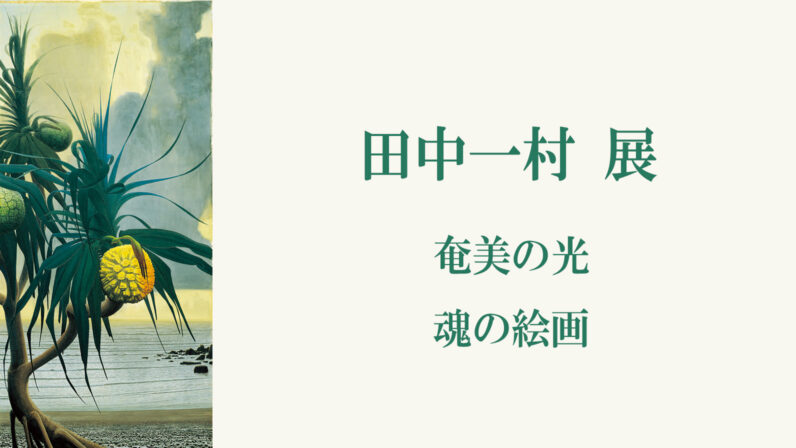

On the other hand, the special exhibition featured a display of all-white works titled Neutral Person.

From the special exhibition Kan Miyake – Neutral Person. The main materials used in the works are paper clay and styrofoam.

In the workshop titled Let’s make a face sculpture of someone close to you! participants used white paper clay. There were many participants, with a noticeable number of families attending.

Kan Miyake shared that it was curator Noi Sawaragi who first introduced him to the idea of this exhibition and workshop, leading to his first visit to Tokamachi. Sawaragi believed there might be a connection between Miyake’s all-white works and the snow sculptures at the Snow Festival.

One of the snow sculptures from the Tokamachi Snow Festival. Like the art pieces, these snow sculptures are spread across a large area. The sculpture in the photo was located near Echigo-Mizusawa Station.

The reason for the all-white, or ‘colorless,’ theme stems from Miyake’s experience working for 12 years as a personal care assistant for people with severe physical disabilities. In the caregiving environment, which takes place in other people’s homes, he realized that it would be smoother to assist if he himself had no ‘color.’

Kan Miyake

Originally from Takasaki City, Miyake graduated from the Sculpture Department of Tama Art University in 2006 and currently serves as a part-time lecturer there. He is known for creating large murals using paper clay and styrofoam, and in 2016, he won the Grand Prize of the Taro Okamoto Award. His work spans a wide range of media, including sculpture, painting, picture books, costumes, video, and performance.

When I first heard this, it gave me a somewhat negative impression, but Kan Miyake sees the idea of being colorless and transparent as a way to connect people with one another.

The snow sculptures at the Tokamachi Snow Festival are created by the locals. Unlike other snow festivals where companies or professionals make the art, these are purely community-driven creations. Miyake-san interprets this as a reflection of the fact that snow sculptures, being colorless, can take on any hue, giving them the power to unite people with different emotions, much like a family. Similarly, in Miyake’s artwork Neutral Person, the artist doesn’t make a final judgment, leaving space for personal interpretation and freedom of expression.

“There are no rules in this workshop. There’s no time limit for creating. Everyone is free to make what they want.”

Looking at the finished pieces already on display, it’s clear there’s a lot of freedom in the approach. Miyake mentions, “I think the pandemic has made us stop looking closely at each other’s faces. In this open space at the museum, if you really take a moment to study the face of someone close to you, you might discover a side of them you never noticed before.” However, some of the works also seem to challenge that idea.

The ‘face sculptures’ of loved ones created during the workshop.

But that’s perfectly fine. Art isn’t meant to limit human freedom; it’s meant to challenge the restrictions placed on it.

Rather than worrying about things like whether a piece might get broken or dirty, especially with works that invite interaction or are part of nature, it’s better to trust in the goodwill of others and the natural flow of things. If anything happens, we can always create again.

Nishihara Nao – Future Human 2

By turning the pulley, the giant hands and feet move.

A good example of this is the snow sculptures, which naturally turn to water as the weather warms. While it may seem anarchic or utopian, it could also be seen as a way of living that respects both others and nature.

There is also a snow sculpture from the Snow Festival in front of the MonET building (only during the Tōkamachi Snow Festival).

Traversing Through Life with The Gangi Spirit

As I thought about this, I remembered a story I heard at the Tokamachi City Museum TOPPAKU at the start of this trip. The museum showcases numerous Jomon period pottery pieces unearthed from the area, including several flame-shaped pots, one of which is even a national treasure.

The flame-shaped pottery at TOPPAKU. One of the national treasures.

“Around 5,000 years ago, the people of this land were already artistic,” the woman from the Tokamachi City Tourism Association proudly said. This area, known for its heavy snowfall, has been shaped by the seasons for centuries. The snow itself created distinct seasonal changes, where food was gathered in the warmer months, and tools were made in the cold months, establishing a life with clear contrasts. It’s believed that to survive the harsh environment, people had no choice but to work together. I’d imagine even among the Jomon people, there must have been some jerks and misfits though.

At TOPPAKU, there’s a diorama showcasing the lifestyle of the people from the Jomon period in this area. In the nearby photo booth, you can choose your favorite Jomon-style outfit, take a picture, and find yourself featured in an animated scene of Jomon life on the background screen.

The second floor of MonET has a spacious corridor, where each large-scale installation is given plenty of room to stretch out and fully express itself.

One of the installations in the MonET second-floor corridor, Ariel by Nicolas Darrot, features a mechanical ‘air fairy’ that dances for five minutes to the rhythm of the music.

There were no bothersome guidelines like ‘look from this angle’ or ‘don’t touch this,’ but walking through the corridor alongside other visitors never felt uncomfortable. By the time I made it around, I was completely exhausted, but spending time with the immersive, experiential works was so enjoyable that I didn’t want to leave.

Traditional houses in Tokamachi were designed with extended eaves on the first floor, so when the town is covered by heavy snow, the eaves create a passageway. This passage was apparently called ‘Gangi.’

A model from TOPPAKU. The eaves of the houses on both sides extend long, creating a passageway underneath. This is known as the Gangi.

Upon reflection, rather than trying to force nature into submission, it’s about fostering a way of life that flows with nature, and creating a place where everyone can live well through small acts of goodwill. To bring this dream to life, this spirit of Gangi may just be the magical secret that Kabakov refers to.

The Echigo-Tsumari Art Triennale (ETAT)

https://www.echigo-tsumari.jp/en/